Chapter eleven of the Book of Genesis tells the story of the Tower of Babel. According to the legend, even before the tower was completed, God foresaw that if humanity succeeded in constructing such an ambitious edifice, they would be capable of achieving anything they set their minds to. To prevent this, He decided to set confusion by introducing different languages, which made communication—and thus construction—unattainable. As a result, the tower was never finished, and people dispersed across the earth. Some modern critics of skyscrapers ironically suggest that God had valid reasons for curbing human overconfidence.

A new wave of high-rise buildings began in the late 1600s. By the 17th century, the streets of Paris were lined with five- and seven-story buildings. The development of iron-framed structures in the 1860s marked another significant turning point. In 1885, William Le Baron Jenney, founder of the Chicago School of Architecture, along with his associate Louis Sullivan, pioneered the design of the first skyscrapers.

Initially welcomed with hope and optimism by architects, urban planners, and housing officials, high-rise buildings—often referred to as “sky cities”—quickly evolved into symbols of dismay and anxiety. Rather than cultivating thriving communities, they became concrete traps, isolating the poorest residents from the world below.

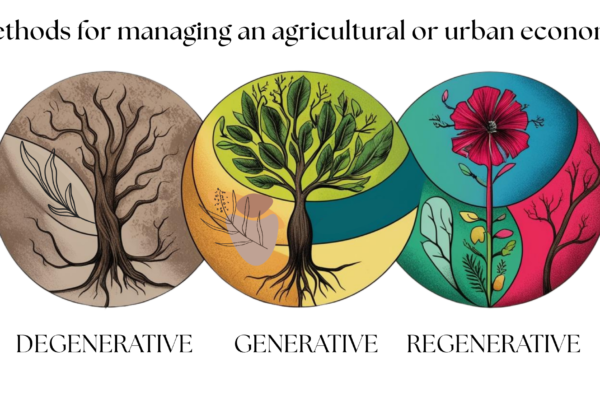

As the population continues to grow, so does the demand for new housing, leading to a predominance of high-rise buildings in urban landscapes. Skyscraper construction is commonly viewed as a solution to the ongoing issue of overcrowding in cities. The economic reforms in China since 1978 have sparked the largest internal migration in history, as millions of rural residents have relocated to major cities in search of factory jobs and the expanding service sector.

While high-rise buildings provide affordable housing solutions, there are concerns about their effects on quality of life from psychological and physiological perspectives.

In 2007, Professor Robert Gifford from Victoria University published an article in the Architectural Science Review titled “The Impact of Living in High-Rise Buildings.” He analysed numerous studies about the psychological effects of living in high-rise environments and conducted nearly one hundred scientific surveys to assess whether these settings enhance or diminish well-being. His research examined various factors, including housing satisfaction, psychological stress, suicide rates (which were found to be significantly higher in high-rise buildings), behavioural issues, crime rates, fear of crime, social connections, and the suitability of these buildings for raising children.

The findings were concerning: only 17% of the studies indicated positive effects, 55% showed adverse outcomes, and 27% had mixed or neutral results. Among the key insights, a substantial body of evidence confirmed that residents of high-rise buildings are more likely to experience mental health issues, heightened fear of crime, weaker social connections, and more significant challenges in raising children.

The Egyptians were among the first to apply scientific principles in constructing their impressive structures. In designing their pyramids, they utilised geometry and astronomy while seeking to understand and incorporate their knowledge of nature and materials. This method allowed them to build massive tombs with precisely fitted blocks, complete with secret chambers and intricate passageways. Similarly, the remarkable construction of Gothic cathedrals in medieval Europe continues to inspire and impress contemporary architects. Despite lacking avant-garde technology and complex computing tools, builders from that era accomplished engineering feats that are still impressive and enigmatic today.

The modern comprehensive study of architecture’s social and psychological effects can be traced back to the Chicago School (e.g., Park, 1925), where researchers began exploring the social ecology of cities. Their work laid the groundwork for numerous scientific studies on housing and its impact on society. By the 1950s, the focus shifted toward personal and physiological factors, examining how architecture influences social behaviour and psychological well-being.

Architecture must consider not only physical and technical aspects but also social, physiological, behavioural, and interpersonal dynamics to create spaces that genuinely support human needs.

Tall buildings are thought to trigger at least six characteristic fears: the concern for a loved one accidentally falling from a window, the fear of being trapped by fire, anxiety about being caught in an earthquake in seismic regions, apprehension regarding potential attacks on skyscrapers following the events of September 11, and the nervousness of sharing close quarters with many strangers. This anxiety can manifest as a fear of crime, social isolation, and the spread of disease in shared spaces.

Research has shown a connection between housing height and mental health issues. Residents living on upper floors of high-rise buildings tend to report more depressive symptoms than those on lower levels. Notably, individuals who move to lower floors often experience an improvement in their mental state, indicating a direct relationship between elevation and psychological well-being.

Satisfaction with high-rise living depends on several factors. People tend to be happier in these buildings if they do not have young children, do not plan to stay long-term, and are socially adept. High-rise living fits certain lifestyles well, but nature enthusiasts like gardeners may struggle without access to balconies or rooftop greenery. Financial status also plays a significant role; wealthier individuals can afford better housing in greener, more community-oriented areas or even maintain a secondary home in the countryside. While older, socially oriented individuals and single young professionals may prefer high-rise living, other demographics often find greater happiness in low-rise housing.

Children living in high-rise buildings often show more behavioural issues than those in low-rise homes. This is influenced by socioeconomic factors and the limitations of high-rise environments, which restrict physical activity and make parental supervision more difficult.

Life in apartment buildings is characterized by both anonymity and depersonalisation. While this can offer privacy and freedom from unwanted social interactions, it often decreases social connections, mutual assistance, and empathy among residents. Despite living in close proximity to many people, residents frequently feel socially isolated. Aside from interactions with immediate neighbours, relationships with others in the building can resemble those with strangers encountered on the street.

The effects of high-rise living can alter significantly and are influenced by various architectural and external factors. These include the socioeconomic status of residents, the building’s location, the presence of children, gender, age, and population density.

Researchers have discovered stronger social connections tend to develop on the lower floors of buildings, particularly up to the fifth floor. This finding has sparked debate, with some experts suggesting that residents on these floors tend to use elevators less frequently, resulting in increased physical activity. Additionally, those living on lower floors have a clearer view of their surroundings. In contrast, individuals on higher floors may feel more detached from street-level life as their distance from the ground increases.

Intrigued by these differences, some scientists decided to study residents’ lifestyles and dietary habits above and below the fifth floor. Another theory regarding the decline in well-being and quality of life in high-rise living is based on a biological phenomenon known as the Bruce effect. First observed in 1959 by British zoologist Hilda Margaret Bruce, this effect describes how pregnant female mice may experience miscarriage when exposed to the scent of an unfamiliar male. Mice primarily communicate through pheromones, and any environmental disruption—such as cage cleaning—can temporarily increase aggression within the colony until familiar scents are restored. This pheromone exchange appears to lower progesterone levels in pregnant females, leading to miscarriage, which ensures that only the dominant male’s offspring survive. In an experiment, researchers placed mice in a long tube with cages at various points and a fan at one end. The mice nearest the fan thrived, forming strong social bonds and reproducing successfully. Those in the middle experienced increased aggression, while those at the far end became infertile. Some researchers have drawn parallels between this phenomenon and human life in densely populated high-rise buildings, hypothesizing that prolonged exposure to crowded living conditions may negatively impact well-being, social relationships, and fertility.

No Comments