“Weeds” are typically seen as unwanted plants that grow aggressively, often overshadowing more desirable vegetation. These “invasive” species can include a variety of flora and sparse grasses that diminish the health and aesthetics of gardens and lawns. In Wikipedia, weeds are characterised as wild plants that grow in agricultural areas, such as vegetable gardens, and can harm crops by reducing yields and lowering the quality of farm produce. The English version of this article defines a weed as a plant considered undesirable in a specific setting, one that has grown in the wrong place. Similarly, Efremova’s Explanatory Dictionary states weeds are unruly plants that displace and suppress cultivated crops. An agricultural dictionary defines them as plants not cultivated by humans and invading agrarian lands.

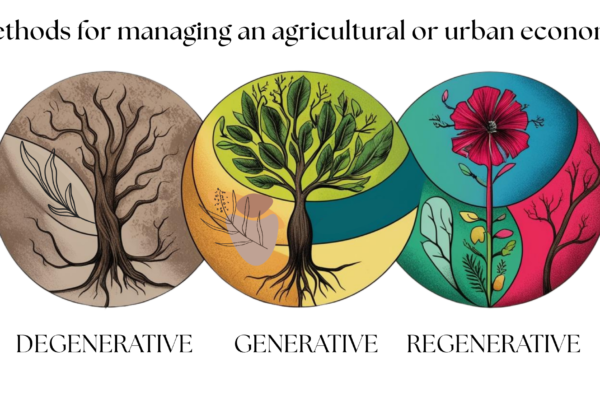

Given humanity’s tendency to demonise what it does not fully understand, I found it intriguing to explore whether weeds truly deserve their negative reputation. Did Mother Nature create these so-called nuisance plants to spite humanity, or do they serve a deeper purpose? None of the above definitions considers factors such as soil conditions, the ecological functions of these plants in problematic areas, or whether our cultivation methods—like the widespread use of monocultures—are in harmony with nature.

Imagine a small patch of land filled with a variety of seeds, each one unique and full of growth potential. However, the type of seed that will take root ultimately depends on the surrounding conditions. This critical factor is often overlooked, even though it is the key to understanding the issue.

The plants growing on your land tell a story—offering valuable insights about the soil and its condition. By learning to “translate” their indications, you can observe and analyse the plants in an area to better understand the health of the soil and identify any imbalances it may have.

Every so-called weed has a purpose and a role in nature. Some, like legumes, help fix nitrogen in the soil, while others provide shade that supports biodiversity. In permaculture, weeds are not viewed as enemies to be eradicated; instead, they are seen as valuable companions in land restoration. Rather than fighting against them, permaculture uses weeds for composting and improving soil quality. Working with these plants is considered an art form that respects natural processes.

Any suburban plot of land you encounter will be damaged in one way or another, and most often, the signs of damage will be written right on the soil’s surface. For example, bindweed, which is so usually called an invader or invasive plant, grows with extraordinary vigour in clay soils; dandelion and thistle “love” acidic soils and wild strawberries live in very acidic soil; field pennycress – are incredibly alkaline. Clover indicates a low level of nitrogen in the soil. Yarrow suggests that the soil lacks potassium.

Instead of just removing these plants, it’s essential to understand the underlying issues they represent. Just like an experienced doctor treats the root cause of an illness rather than merely addressing the symptoms, we should examine and resolve the soil problems these plants indicate.

Wild plants, constantly dismissed as nuisances, are ecological pioneers—nature’s “paramedics” that help heal the land. These pioneer plants respond to human-caused disturbances, such as agriculture and deforestation, and natural disasters like wildfires. They quickly stabilise damaged areas by anchoring the soil when it becomes exposed. Rain and wind can strip away topsoil and its nutrients without this protection, leading to erosion and desertification. This way, pioneer plants prevent further soil loss and create conditions for other life forms to return.

Beyond stabilising the land, these plants also enrich the soil. They decompose and release vital nutrients into the earth as they complete their short life cycle. Once the soil has regained health and balance, these plants naturally fade away, allowing other forms of vegetation to take their place.

When an area is overrun with weeds, it often indicates that the land needs rest and repair. Some experienced land stewards even plant fields with clover and dandelions, allowing them to grow for a year to help replenish the soil.

Because cultivated land is constantly harvested, nutrients are continuously removed, making it challenging to maintain fertility at the same level as a natural forest. This means that weeds will always return in some form. However, instead of trying to eliminate them, they can be utilised as valuable natural mulch, contributing to the ongoing cycle of soil regeneration.

In one of his lectures, Geoff Lawton, a well-known permaculturist, illustrates an imaginable plot of land divided into four sectors, each representing a different type of soil disturbance. By understanding the plants that naturally grow in response to these disturbances, we can learn to work with nature rather than against it.

In the first square, he imagines a fire swept through the area. The plants that emerge afterwards can fix potassium in the soil. Instead of removing these plants, we can use them as mulch to enrich the potassium levels when necessary. The second square represents heavily compacted or rammed soil. Here, plants with long, strong roots take over—challenging to pull out, yet essential for breaking up the soil and restoring its natural structure. In the third square, he considers the contrasting problem: ploughed land. In response, plants like ageratum and hairy Bidens emerge. Their intricate, branched root systems act like a web, stabilising the topsoil and preventing erosion. The fourth square illustrates an area where nitrogen fixation is required. Numerous legumes and pod-bearing plants thrive in this area. Their roots host special nodule bacteria—organisms that convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia, making it available for plant growth. In return, the plants provide the bacteria with sugars from photosynthesis and create the low-oxygen conditions they need to function.

Lawton encourages his students to stop seeing weeds as enemies and to instead examine the conditions that allow them to thrive. Understanding why certain plants grow in specific environments will enable us to utilise their natural functions to restore and maintain healthy soil.

No Comments